NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. — Astronomers have for the first time been able to see the innards of an exoplanet directly.

Some 800 light-years away, this Neptune-sized world is spilling its guts into space. The James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST, recently spotted the event. Astronomers described what they’ve gleaned from those entrails here on January 14 and 15 at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

“If this is true, it’s super cool,” says Mercedez López-Morales of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Md. She’s an astronomer who was not involved in the new work. “For the first time,” she says, “you can study directly what the interior of an exoplanet is made of. That’s exciting.”

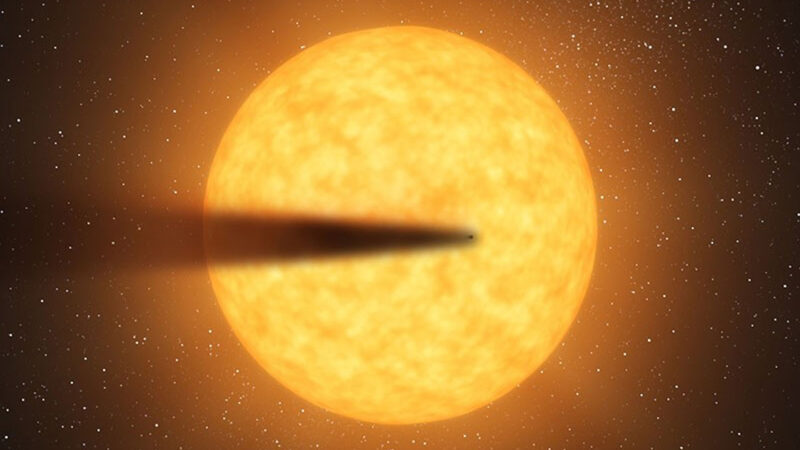

The exoplanet — K2 22b — was discovered in 2015. It sits scorchingly close to its star, completing an orbit in just nine hours. It’s too small to be seen itself. However, it periodically emits clouds of opaque dust. They create a cometlike tail that blocks a small share (less than 1 percent) of its host star’s light.

Astronomers soon realized that the dust was probably cooled magma from the exoplanet’s interior. This trail of planetary viscera offered a unique chance to tease out the chemical composition of K2 22b’s mantle. (That’s the material right below a planet’s crust.)

Getting clues to any planet’s mantle, even Earth’s, is challenging, says Jason Wright of Penn State in University Park. He’s an author of the new study. And, he notes, “When nature gives you a gift like that, you have to take it.”

Studying the exoplanet’s trail

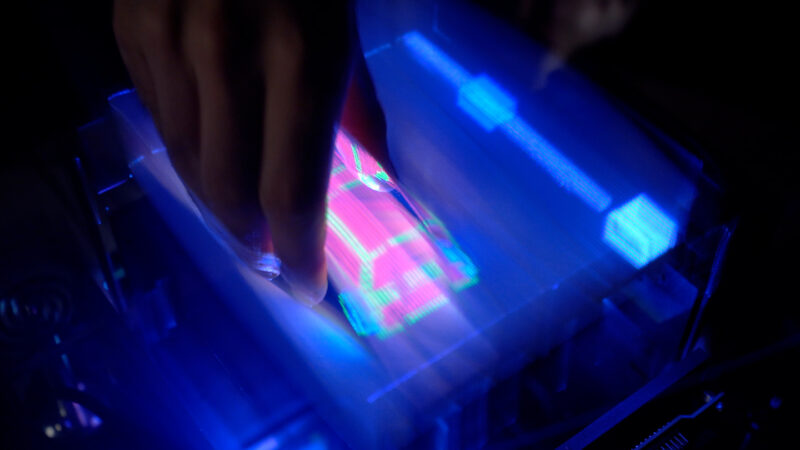

Wright was part of a team that observed K2 22b with JWST’s sensitive mid-infrared spectrometer last April. Different minerals in the dust emit particular wavelengths of light. This allowed the team figure out what the exoplanet is made of.

The dust doesn’t seem to be pure iron. That’s what scientists would have expected if the planet was a bare core with no mantle or crust jacketing it. “There is still meat left on the bones, so to speak,” said astronomer Nick Tusay. He was describing the planet January 14 at the meeting.

Something in the dust emitted light that was hard to link to any specific material, he said. His team first checked to see if the dust grains were magnesium oxide and silicon monoxide. Those are what you’d expect in mantle material. But the emitted light didn’t fit these minerals.

Surprisingly, the dust looks most like nitric oxide and carbon dioxide from vaporized ices, Tusay said. “If that’s true, what we’re looking at is a snowball disintegrating.”

Those gases are hard to explain for a planet so close to its star. “It’s just so weird and unexpected,” Tusay said. In an attempt to learn more, he has requested more JWST observing time.

He and his team have also reported their results in a paper submitted January 14 to arXiv.org. This is a website where new data are stored and can be viewed prior to peer review.

López-Morales agrees that more observations are needed to confirm the planet’s makeup. “It’s very preliminary, very promising, definitely needs more data,” she says. Studying a handful of other known disintegrating exoplanets would be interesting, too.

A newly discovered disintegrating planet might be the best place to start. The space-based TESS telescope discovered this new planet in October. It’s emitting a dust cloud so big that it extends halfway around its host star in a horseshoe-shaped tail some 9 million kilometers (5.6 million miles) long. Astronomer Marc Hon of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology reported this at the meeting on January 15.

This is the closest disintegrating planet to Earth yet discovered. For that reason, its contents will be even more clear in JWST’s data.

“We’ve proved we can do it with K2 22b,” Tusay says. “This one will be better.”