Scene: A patrol boat cruises through the water, just off a Caribbean island. Cue the pounding drums — a movie-trailer signal that danger approaches.

Enter Spinosaurus. Three large, spiny sails slice through the deep blue sea and begin to circle the boat. The water roils. A worried passenger wonders what they are.

Cut to another passenger who clings to the boat as it lurches. Suddenly, a spiny-sailed terror surges from the ocean, jaws snapping.

That scene comes from the trailer for Jurassic World Rebirth. It’s set to appear in theaters this summer. The movie brings a controversial dinosaur — Spinosaurus — back to the Jurassic Park series. When last onscreen — in 2001’s Jurassic Park III — Spinosaurus had stalked the movie’s heroes through a jungle.

This time, based on a recent wave of research, Spinosaurus swims.

To paleontologists, the idea that any dinosaur swam would be a game changer.

The Age of Dinosaurs lasted from about 240 million years ago to 66 million years ago. That’s most of the Mesozoic Era. It’s when dinosaurs dominated Earth. More than 1,000 known ancient species of dinosaur — excluding birds — stomped, grazed and scampered across every continent, including Antarctica.

And every one of them was a landlubber. The seas and rivers — those were the domains of other creatures.

That thinking has changed in the last decade. Some paleontologists are now proposing that a series of weird body parts on Spinosaurus makes the most sense when viewed through a watery lens. This dinosaur, they argue, must have lived mostly submerged.

That hypothesis remains highly controversial. It has begun fueling new research and popular interest in this quirky creature.

Indeed, confirming the ability of Spinosaurus to swim would be nothing short of a blockbuster discovery.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Reading the bones

This behemoth didn’t need to swim to be a standout among dinosaurs. Take its size. At 15 meters (50 feet), it was the longest predatory dino ever found. Its body was bigger than a Tyrannosaurus rex. Its head boasted a narrow, crocodile-like snout. A long, flat, paddlelike tail brought up its rear. And the sail rising from its back? That was taller than a human.

“It’s bizarre-looking, even by dinosaur standards,” says Thomas Holtz. A vertebrate paleontologist, he works at the University of Maryland in College Park.

Spinosaurus looked nothing like other familiar predatory dinos, such as T. rex or Velociraptor. Even among its closest kin (a group known as spinosaurids) Spinosaurus was … kind of extra, Holtz says. “The proportions — what we know of them — are weird, even for a spinosaurid.”

Any attempt to imagine an extinct creature’s habitat and lifestyle begins with its bones. But that’s a problem here. Unlike other well-known meat-eating dinosaurs, Holtz notes, “we do not yet have a single good Spinosaurus skeleton.”

The first of its fossils turned up in 1912 at the Bahariya Oasis. That’s in western Egypt. The findings consisted of a lower jaw and some crocodile-like teeth. There were also a bunch of backbone pieces with spines up to 2 meters (6.6 feet) tall. But that’s all.

These fossils were truly unusual. In fact, they were so distinct that German paleontologist Ernst Stromer decided they must belong to a newfound creature. He named it Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. (Even today it’s the only agreed-upon species in its genus.)

For decades, those fossils lived in a museum in Munich, Germany, as the sole Spinosaurus specimens.

Then, during World War II, Allied forces bombed Munich. This destroyed much of the museum and its fossils. Fortunately, Stromer had made detailed sketches of the Spinosaurus bones. Until about 2009, his sketches were nearly all any researcher had to go on.

Paleontologists returned to the Bahariya Oasis again and again. But no more remnants of this species showed up. Then in 2008, Nizar Ibrahim visited a museum in Milan, Italy. This vertebrate paleontologist works at the University of Portsmouth in England. And in that Milan museum he spied recently acquired jawbones from a Spinosaurus.

Its bones, Ibrahim learned, had been purchased from a fossil hunter from the North African country of Morocco. To learn more, Ibrahim decided to track this man down. At the time, he knew little of him, however, other than that he had a mustache. Against all odds, Ibrahim spotted this dealer in a Moroccan bazaar. He persuaded the man to lead him to where the bones had been found. It turned out to be a remote desert in Morocco’s Kem Kem region.

Ibrahim followed the fossil hunter’s puttering motorcycle up and down steep slopes. Hours passed and gas began running low, Ibrahim recalls. He wondered if they’d ever get back out.

But it was worth the trip. The Kem Kem beds turned out to hold a wealth of fossils. Among them: surprise details about Spinosaurus.

The life aquatic

Ibrahim’s team described its analyses of these bones in a 2014 Science paper. After a century-long gap, these new Spinosaurus details were thrilling. But the real stunner was a suggestion that this creature might have been largely aquatic.

Today’s arid, windswept Moroccan Sahara had been much wetter in the past. Some 100 million years ago, Earth’s average sea level was about 200 meters (660 feet) higher than it is today. A vast seaway covered much of the northwest African nations of Algeria, Mali and Niger.

Researchers had suspected Spinosaurus ate a lot of fish. Ibrahim’s team outlined new evidence for its having an aquatic life. Spinosaurus’ limb bones were dense. They were like the bones of penguins or manatees, animals that evolved to live in water. Dense bones help those animals control how much they sink or float.

Its hip bones and back limbs suggested Spinosaurus didn’t move on two feet, like other meat-eating dinosaurs. Instead, it likely used all four limbs to get around — as might be needed in water.

This dino also had cone-shaped teeth. They would have easily snagged slippery fish. And its nostrils sat far back from the tip of the snout. That would have helped this predator breathe easily while swimming.

Again and again, Ibrahim went back to the Kem Kem site. In 2020, he announced another headline-grabbing find: a nearly complete tail. Again, it was very weird. Running nearly as long as the creature’s body, it was topped by tall spines that formed a tail fin.

That tail helped flesh out a picture that Ibrahim and his team were building of a water-dwelling dinosaur.

This tail was ideal for water propulsion, they reported in 2020. Its flexibility allowed for a wide range of movements, including swinging sideways. They tested a robotic version of the tail. It performed like such semiaquatic swimmers as crocodiles. (Semiaquatic means a creature goes in water often but doesn’t dwell fully in water.)

Spinosaurus, the team concluded, used its tail to powerfully slice through water. It likely actively swam to pursue prey. It was, in short, a water monster, not some land terror.

Artistic sketches of this version of Spinosaurus showed it chasing prey underwater with jaws snatching, legs paddling and long tail slashing sideways. The public snapped up this version. It was compelling and fun.

But to some paleontologists, this vision goes a bit too far.

Watery whiplash

Among those scientists were Holtz and David Hone. Hone, too, is a vertebrate paleontologist. He works in England at Queen Mary University of London. In 2021, the two men penned a swift response to the tail paper. The evidence was compelling, they said. It also was far from conclusive, they wrote in Palaeontologia Electronica. Sure, Spinosaurus might have lived near water and hunted in it.

But, they argued, there wasn’t enough evidence to show it could swim or chase prey underwater.

Instead, they proposed this dinosaur was more like a heron than a crocodile. Herons wade in the water and fish from the shore or by wading in shallows. As for the tall sail and the paddle-shaped tail, those were just showy displays for mating or other social behaviors, they said.

Paul Sereno also was skeptical that this dinosaur could swim. He’s a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Chicago in Illinois. Dense bones don’t prove an animal can swim. Hippos have dense bones, too. But they walk on riverbeds or lake bottoms.

Sereno is part of a team that studied Spinosaurus bones. To them, this dino’s bones weren’t even all that dense. And they probably were too small to help control how much the animal floated, this team concluded in 2022. Working from models, they showed an animal that could walk the land on two legs. In the water it was unstable and slow. It also was too buoyant to successfully dive.

Offbeat family

Every time a new bit of Spinosaurus turns up, people scramble to reimagine the creature’s form and how it might have behaved. But much remains uncertain about the layout of its fat, muscles and other soft tissues. Any attempt to figure out how this dino moved and lived raises a lot of questions.

For instance, its utter weirdness means that there aren’t any obvious living comparisons. “It is an animal that’s so different from anything alive today,” Ibrahim says — which is “wonderful.”

Ibrahim sees the debate on just how aquatic Spinosaurus was as quibbling over small details. In the end, he finds, Spinosaurus “is an animal with lots and lots of aquatic adaptations.”

Studying its extinct family members might also help bring Spinosaurus into focus.

As Tyrannosaurus rex is to tyrannosaurs, so Spinosaurus is to spinosaurs. It’s the one you imagine when picturing this group of dinosaurs. Spinosaurus is like its cousins — only bigger, stranger and more exciting.

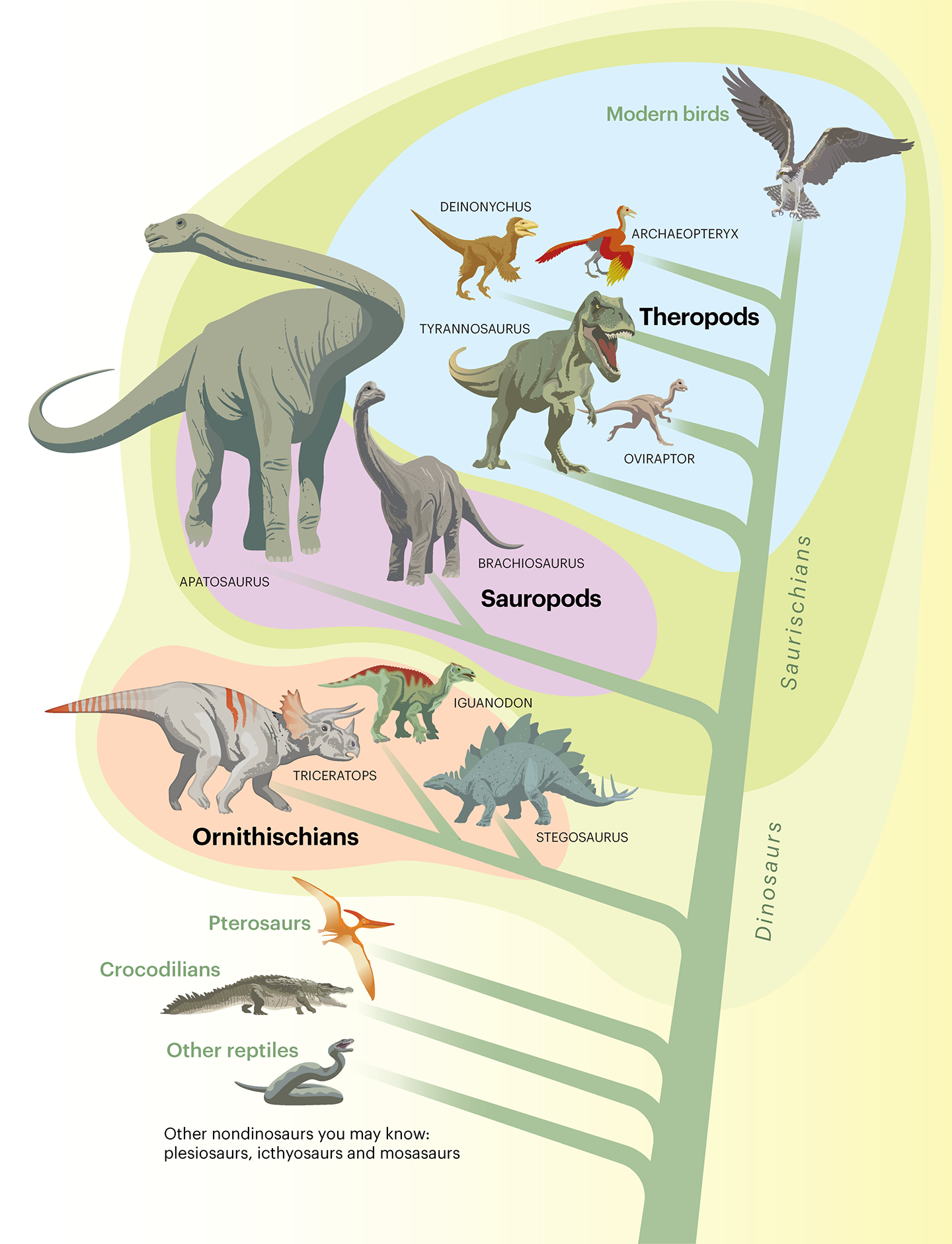

Spinosaurids were theropods. That’s a fierce and fascinating branch of the dinosaur family tree. It includes other sharp-tooths, such as tyrannosaurs, allosaurs and velociraptors. There are some dozen or so different types of spinosaurids.

“There’s a lot of things that we don’t know about this group,” admits Jingmai O’Connor. She’s a vertebrate paleontologist at Chicago’s Field Museum.

Few remain of Spinosaurus’ relatives exist. For instance, the only known fossils of the spinosaurid Oxalaia quilombensis were in a museum in Brazil. And they were destroyed in a 2018 fire.

But all spinosaurids do show some adaptation to water. Like Spinosaurus, they all had a long, narrow, crocodile-like skull. Their nostrils sit farther back on their heads than those of other theropods. And a bony crest rises near the middle of their skull. Many, but not all, also sport a tall, spiny sail atop their backs — though none as tall as on Spinosaurus.

Then there are their conical, straight teeth. They’re designed for snagging food, not sawing through it. And, O’Connor adds, “They’re the only group of dinosaurs that seems to be specialized to primarily eat fish.”

Researchers have used these close cousins to try to better understand Spinosaurus.

María Ciudad-Real is a vertebrate paleontologist at National University of Distance Education. It’s in Madrid, Spain. Her team used parts of Suchomimus to fill in missing parts of a Spinosaurus’ skull.

Spinosaurus had less space devoted to smell and more to its eye sockets, they found. That might be useful for living in water. It also appears to have bent its head down like a heron would while scanning the water for food. Ciudad-Real shared these findings in 2023. It was at the annual meeting of the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP).

Based on its relatives, Spinosaurus’ teeth may have been powerful. Most of its bite force was toward the back of the jaw. That’s according to Evan Johnson-Ransom, a University of Chicago paleontologist. He, too, shared his team’s findings at the 2023 SVP meeting. That suggests, he said, that crocodiles aren’t a great comparison for spinosaurids.

But feeding is a whole-body effort, Sereno says. He was part of a team that measured features of the skull, neck and hind limbs for Spinosaurus and Suchomimus. They wanted to see how these stacked up against other creatures. Those included nonbird dinosaurs, modern reptiles (such as crocodiles) and modern birds of prey.

The spinosaurids were closest to long-necked semiaquatic birds — such as herons. Sereno’s team will share its findings soon in PLoS ONE.

These lines of evidence suggest spinosaurids were waders, Sereno says. The group might have been becoming more aquatic. But as for swimming: “I just don’t think it’s gone that far.”

Enduring mystery

What’s needed to better understand an extinct animal? More bones.

That’s driving Ibrahim to keep looking for more Spinosaurus finds. His trips to the Kem Kem beds continue to turn up treasures. Hundreds of new bones may point to even more new insights into the weird dino.

Other researchers are also still on the hunt. Sereno announced the discovery of a partial skeleton of a never-before-seen Spinosaurus species at the SVP meeting last November. The fossils included a skull with a curved crest. It’s the tallest ever reported on a predatory dinosaur.

That lends weight, Sereno says, to the idea that the tall sail and tail fin on this dino might have been for showing off, not swimming. And this creature definitely was not a swimmer, he argues. It was found thousands of kilometers away from any water that would have been deep enough to swim in.

Meanwhile, in pop culture, Spinosaurus’ star continues to rise. It’s even getting its own episode in the upcoming TV nature documentary: Walking With Dinosaurs 2. Due out June 16, it’s a sequel to the 1999 TV miniseries with that name.

Ibrahim advised the show makers on the science for their Spinosaurus episode. It was the first dinosaur chosen for new series, Ibrahim says. After all, he notes: “Spinosaurus is very much the superstar.”