In the world of Harry Potter, memories can be manipulated with the flick of a wand. Albus Dumbledore reels wispy memories out of his head and puts them in a Pensieve. If he later dunks his head in that magical basin, he can see his past experiences with lifelike clarity. Hermione Granger, meanwhile, uses the spell Obliviate to remove herself from her parents’ memories to protect them from the wizarding world.

In real life, memories are not storable liquids or files that can simply be deleted from people’s brains. “I find memory very difficult to define,” says André Fenton. This neuroscientist studies memory at New York University in New York City.

To make a memory, a person needs to experience something. This could be riding a bike, losing a tooth or playing with a pet. Then electricity courses through connections between the nerve cells, or neurons, in their brain, Fenton says. This electrical activity can strengthen those connections. The more exposure to an experience someone has, the stronger those connections become. These connections can also weaken over time, leading to forgetting.

The power to make someone perfectly remember or completely forget something is still mere fantasy. But some researchers have taken early steps to strengthen or weaken people’s memories. That work could help people suffering from disorders like Alzheimer’s. This is a disease in which people can lose their memories. Or it could help people with post-traumatic stress disorder. This PTSD is a condition in which people might suffer from memories they don’t want to have.

The hippocampus (yellow) is a part of the brain involved in storing memories. THOM LEACH/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Getty Images

Storing memories

Neuroscientist Robert Hampson is fascinated by the idea of the Pensieve. “I love to see the idea of being able to pull a memory, store it, look at it, examine it,” he says. Hampson studies memory at Wake Forest University School of Medicine. That’s in Winston-Salem, N.C.

He and his colleagues haven’t found a way to store past experiences like leftovers in magical dishes. But they have found that giving tiny electrical zaps to people’s brains could help them form stronger memories.

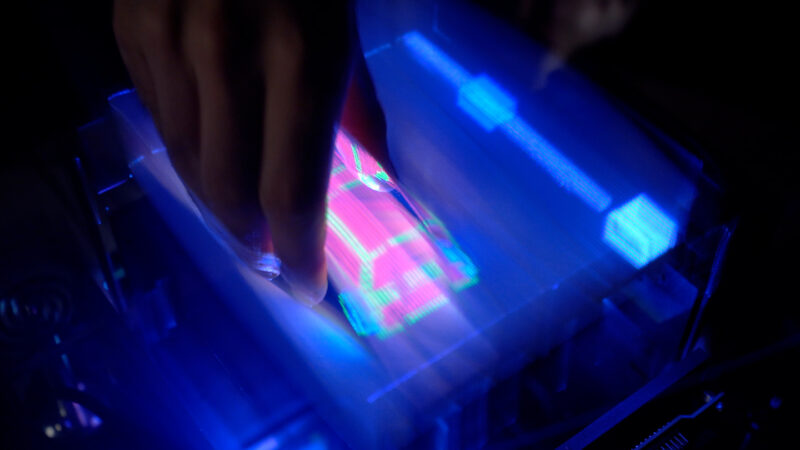

In one experiment, Hampson’s team placed wires about as thick as a strand of hair in the brains of 17 patients with epilepsy. (The researchers chose patients with epilepsy because they often have wires placed in their brains to map and understand their seizures.) The wires recorded the electrical activity of brain cells in the hippocampus. That’s a part of the brain that processes memories.

Patients then looked at a picture on a computer screen. A few seconds later, the screen showed that same picture, plus three different pictures. Patients were asked to choose the picture they had first seen. They repeated this process 100 times, then took a short break.

Afterward, patients were shown 100 more pictures. These included pictures they had seen in the first part of the experiment. There were also pictures they had never seen. The patients were asked to touch the picture they were most familiar with.

When we see a picture, electrical activity courses through our brains, says Hampson. But this electrical activity was different for every picture. Hampson’s team studied the electrical patterns produced when nine patients saw pictures in their sample. Then, the researchers could use math equations to mimic the patterns.

The researchers applied tiny zaps that mimicked those electrical patterns to the other eight patients. In picture memory tests, the patients’ memories for images paired with the small jolts improved by 35 to 40 percent. Their memory did not improve for pictures not paired with the zaps.

In the future, brain implants that deliver such tiny zaps might be used to boost memory. The researchers aren’t sure when this tech will be ready for widespread use. “The first users would likely be people suffering from a disease such as Alzheimer’s disease,” Hampson says. “Or from a head injury that results in damage to the parts of the brain associated with memory.”

Erasing memories

Other scientists, meanwhile, are looking into whether it’s possible to help people forget certain memories. This research is still in its earliest stages. But experiments in animal cells suggest it might someday be possible.

When people sense things, such as the colors of a beautiful painting or the touch of a soft flower, that activates some neurons. This changes where in the cells many molecules are found. That affects how the nerve cells work and, in turn, how they connect to each other. Such altered connections encode, or store, the memory of the experience. The things we give more attention are more likely to be encoded.

But “you can interfere with that encoding,” says Samuel Schacher. He is a retired neuroscientist based in New York City. He and his colleagues found they could manipulate memory encoding in an experiment with sea hare neurons.

The researchers worked with a circuit of three nerve cells. One was a motor neuron. That’s a nerve cell that causes muscles to move. Connected to that motor neuron were two sensory neurons. Those nerve cells process information from the environment. By making molecular tweaks to those nerve cells, the scientists were able to erase the memory-storing connection between the motor neuron and one of the sensory neurons.

This hinted it could be possible to erase some memories while leaving others intact. And perhaps someday, new therapies could coax neurons into letting go of specific unwanted memories.

Experiments on cells from sea hares like this one hint that it may one day be possible to erase unwanted memories.divedog/Shutterstock

People with some mental health conditions might benefit from such memory wiping. Take people with PTSD. When someone has this condition, traumatic memories can cause their mind to link a neutral experience to a dangerous one, says Schacher.

“But you don’t want to erase the fact that other behaviors associated with the bad event may be useful to remember,” says Schacher.

While this science worked in sea hare cells, it’s far from being used in people. In the meantime, there are a few medications and therapies that exist for helping people cope with traumatic memories, says Schacher.

Ethical questions

In some sense, “we’ve been trying to manipulate memories forever,” says Fenton. For example, when we practice a sport, we are purposely strengthening our memories of how to move our bodies in certain ways. Likewise, if we choose not to study something, we allow ourselves to forget certain information.

But in each of these cases, we’re manipulating our memories through lived experience.

Is it okay to make or erase memories instantly, no experience needed? “The ethics of that are very thorny,” says Fenton. Our lived experiences — and memories of them — make us who we are. Changing a person’s memories could, in some ways, cause them to be a different person, Fenton says. “We must proceed very carefully.”