In the second The Lord of the Rings movie, The Two Towers, an army of treelike creatures called Ents slowly marches to war. They walk for miles through thick, dark forests. Once they arrive at Saruman’s fortress, the Ents unleash destruction. They hurl giant boulders, climb over walls and even rip open a dam to wipe out their enemy.

For trees, the Ents are quite athletic.

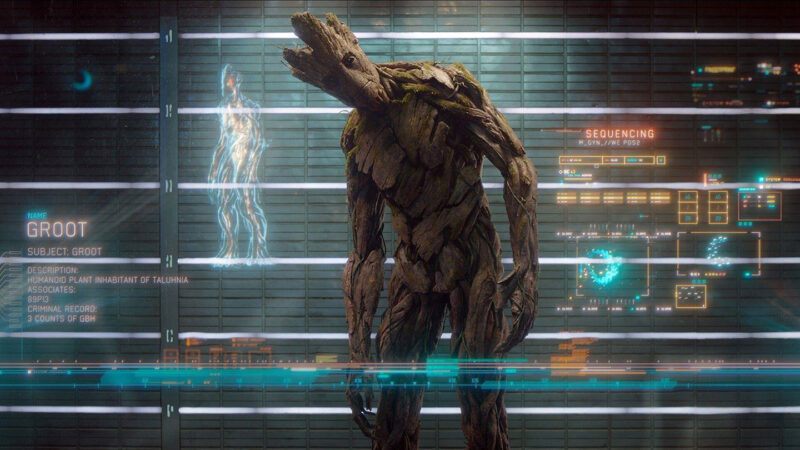

Such active trees can be found throughout science fiction and fantasy worlds. The treelike alien Groot from Guardians of the Galaxy uses twiggy wings to fly through the skies. Trees called Evermeans will walk toward and fight the main character Link in the The Legend of Zelda video games. And Harry Potter’s Whomping Willow — well, it whomps anyone who gets too close.

It can be hard to find the similarities between such agile fictional trees and the seemingly still forests we see in real life. But science has shown us that trees and forests do move. They’re just really, really slow.

Searching for light

All trees move as their seeds grow into saplings, stretching up toward the sun. Saplings need sunlight and water to develop. But when they sprout in a place where the sun is blocked by shade, they have to work for those nutrients.

A tree “needs to find enough food. In this case, solar energy,” says Gerardo Avalos. He’s a plant physiologist at the University of Costa Rica, in the province of San José. By slowly stretching their branches in a sunny direction, trees can orient themselves to get the most “food” possible. This light-chasing phenomenon is called phototropism.

The walking palm tree can supposedly travel up to 20 meters (some 70 feet) per year, but there’s no scientific evidence to support this.Wagner Campelo/Shutterstock

While trees can stretch and move their appendages, it’s very different from how humans and Ents move. No one comes up and whispers to a tree about where to find water and sunlight. Instead, a tree’s hormones send messages to encourage growth when the tree needs more light or water.

Tree roots move too. When they sense moisture in surrounding soil, trees will push their roots toward the likely water source. While searching for water underground, roots have found wells, plumbing and pipes. “Sometimes they get into people’s toilets,” says Avalos. One minute, it flushes like it should. And then, “all of the sudden, there’s something wrong with the toilet!”

In addition to destroying people’s bathrooms, funky-looking roots have also inspired folklore. Some scientists and tour guides tell of a walking tree in the tropical forests of South and Central America. This walking palm tree (Socratea exorrhiza) can supposedly travel up to 20 meters (about 70 feet) a year. The palm has roots that grow above ground and look similar to octopus tentacles. Some people have hypothesized that the tree uses these roots to search for light across the shady forest floor. Images of walking palms seemingly sliding down steep hills have inspired some of the folklore, explains Avalos.

“They say that the palm was walking,” he says. “Crossing creeks, going up and down the slopes.” But according to Avalos, the notion of a tree getting up and walking in real life is “pretty ridiculous.” There’s no concrete scientific evidence this happens.

Forests on the move

While individual trees can’t cross rivers and climb mountains, entire forests can. And climate change is making their journeys treacherous.

Forests don’t migrate like monarch butterflies, which fly back and forth in tempo with the changing seasons. Instead, forests migrate to compensate for long-term changes in their habitats.

“Trees have been migrating forever,” says Leslie Brandt. She’s an ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service in St. Paul, Minn. During the last ice age, when the Laurentide Ice Sheet covered most of Canada and the northern United States, many tree species took refuge in warmer, southern climates. They didn’t walk or fly there. Instead, forests moved over the course of many generations, through spreading seeds and new tree growth.

“There are seeds, like acorns, that squirrels will pick up and move around,” says Brandt. Think of Scrat dragging his prize acorn to the ends of the earth in Ice Age. Maple tree seeds are encased in tiny “helicopters” that help them soar with the wind. Berries contain seeds that birds eat and poop out. These features can spread seeds out in all directions. But seeds don’t have equally good chances of growing in all places.

While trees can’t walk around on their roots, entire forests can migrate when the wind or birds or other animals move seeds to new places.scott mirror/Shutterstock

As northern habitats got colder during ice ages, for instance, it was likely easier for seeds to thrive toward the warmer south. As a result, more new trees started growing on the southern edges of forests, while older trees up north died out. Slowly, forests migrated, moving around 100 to 500 meters (about 300 to 1,600 feet) a year, Brandt says.

But now, human-caused climate change is changing habitats faster than forests are prepared to move. Mangrove forests, which grow on seacoasts, are under threat from rising oceans. Warmer temperatures in Canada are making it difficult for white spruce to grow. And pinyon pines are struggling with drier climates in the American southwest.

“Trees just cannot keep up,” says Brandt. “Their habitats are changing faster than they can migrate. So, humans are helping them out by moving them.”

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

To give forests a leg up, some scientists are planting new seeds in areas with favorable conditions. This is called assisted migration. Sometimes, assisting migration can even mean replacing species that are no longer equipped to handle a changed landscape with species better suited to the new conditions.

In Minnesota, Brandt is studying trees on the banks of the Mississippi River. The area is flooding more frequently and severely, and invasive beetles are destroying the forests. Floodplain trees like silver maples are dying and struggling to grow.

“We’re looking to replace the trees that are lost with those that are better adapted to the current climate,” says Brandt. Planting trees that thrive near water, like cottonwoods and willows, could be part of the solution.

Nearby, the Superior National Forest just created an assisted migration plan — a guidebook to help forest managers prepare for climate change. Because trees can hold cultural significance, the team has been working with scientists, Minnesota residents and local Indigenous tribes to make sure the forest migration plan aligns with community needs.

Even though forests need to adapt in order to survive climate change, “we don’t want to completely change the forest,” Brandt says, because people “rely on those trees.”