Across the river from Washington, D.C., sits Potomac Overlook Regional Park. Hiking paths wind through acres of forest and cultivated land. Peer into the thick woods and you may glimpse a chipmunk or even a deer. And at the visitor center, there are real-life dinosaurs.

One of these is Twiggy. Sitting on her caretaker’s arm, her massive brown eyes blink in the afternoon sunlight. Ribbons of brown and white streak her chest. This mimics sunlight hitting speckled tree bark. Her long black talons squeeze into a leather glove on which she’s perched.

“When Twiggy is gripping my glove, I feel every bit of it,” says Matt Felperin. At NOVA Parks in Arlington, Va., Felperin works as a naturalist. Twiggy will join Felperin and the other dinosaurs in his care for a raptor show later in the day.

Twiggy is a barred owl. These birds of prey can be found throughout much of eastern North America. Other dinosaurs at the park include Squeaker, the red-shouldered hawk. She chirps as she snacks on mice. And there’s pint-sized Smoke. An Eastern screech owl, he weighs about as much as a baseball.

“When people think ‘dinosaur,’ [what] immediately pops up is, like, a Stegosaurus,” says Jingmai O’Connor. “Or something that’s just not closely related to birds at all.” But for O’Connor and many other researchers, birds are dinosaurs, too. At the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Ill., O’Connor studies how early birds evolved.

“Birds are feathered dinosaurs,” agrees Hans Sues. He’s a curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Smithsonian Museum of History in Washington, D.C. Birds are a subgroup of dinosaurs, which, in turn, are a type of reptile. Evolutionarily speaking, this makes birds “feathered reptiles,” he says.

Over the past 150 years or so, paleontologists have unearthed this connection through fossils. At first, the idea that birds are dinosaurs ruffled the feathers of the scientific community. But fossils have helped researchers piece together the true origins of birds. These are some of the discoveries that have helped to unveil what makes today’s birds so unique.

The first bird

Some 150 million years ago, a creature washed into a shallow sea in what is now Germany. About the size of a crow, it sported black wing feathers. Its arms were tipped with claws, and rows of teeth filled its snout. The body churned in a cloud of silt before sinking to the riverbed. Soon, its body disappeared completely, buried under layers of fine sediment.

This scenario may explain how some fossils of Archaeopteryx formed. Its discovery in 1861 helped scientists first understand the connection between birds and dinosaurs, says Roger Benson. At the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, he studies how reptiles evolved. “Archaeopteryx contains a lot of information about what the ancestor [of modern birds] would have looked like.”

These fossils showed an animal with flat, asymmetrical wing feathers similar to today’s flying birds. In modern birds, such feathers improve lift and stability during flight. But unlike modern birds, Archaeopteryx sported teeth, clawed wings and a long, bony tail.

Researchers quickly noticed this mishmash of reptilian and birdlike features, says Benson. Some used Archaeopteryx to argue that dinosaurs were a stop on the evolutionary tree between reptiles and birds.

But there was one key clue in the Archaeopteryx fossil. Unlike other dinosaurs discovered at the time, Archaeopteryx had a wishbone. Reptiles don’t have this bone. Modern birds do. Because of this, scientists at the time saw Archaeopteryx as the first bird.

Researchers wouldn’t find dinosaurs with wishbones until much later. So at the time, the debate over whether dinosaurs were related to birds fizzled out. “For the next 60 years or so, [scientists thought] birds and dinosaurs had no connection at all,” says Sues.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Not your typical dinosaur

A 3-meter-long (10-foot-long) dinosaur stalked across a wide, flat grassy plain 115 million years ago. This was in what is now Montana. A small, mouselike mammal scurried from a nearby bush. The dinosaur pursued, catching up in a few strides. It pinned its prey with a long sickle claw before tearing it apart with its teeth.

Meet Deinonychus. This dinosaur wasn’t a bird. Instead, it belonged to a group of closely related dinosaurs called dromaeosaurs. When paleontologist John Ostrom discovered it in the 1960s, it helped to reignite the debate over whether birds and dinos were related.

To Ostrom, Deinonychus very much resembled Archaeopteryx. He kept finding “more and more unique similarities between this group of meat-eating dinosaurs and early birds,” says Hues. This included wrist bones similar to those in both Archaeopteryx and modern birds. That would have given Deinonychus very flexible wrists, an adaptation researchers see as a necessary step toward evolving flight.

There also were similarities in the shapes of their hands, pelvises and feet.

Deinonychus and other dromaeosaurs belong to a group of two-legged, mostly meat-eating dinos called theropods. (This group also includes Tyrannosaurus rex.) Ostrom used his observations of Deinonychus as evidence that modern birds descended from theropods. Today, researchers agree that birds arose from small theropods some 160 million years ago.

Ostrom’s work ushered in renewed interest in how dinosaurs moved and behaved. During this “Dinosaur Renaissance,” researchers began moving away from the idea of dinosaurs as sluggish, cold-blooded animals. Some dinosaurs, it appeared, were intelligent and warm-blooded — like today’s birds.

Still, most paleontologists remained doubtful that modern birds descended from dinosaurs. It would take another 20 years to find evidence that convinced those skeptics.

Ruffling feathers

A small dinosaur perched on a branch in a forest some 125 million years ago. The site was in what’s now northeastern China. The animal yawned. Bristling long, iridescent black feathers on its arms and legs took on the appearance of four wings. A tree crashed in the distance, causing the dino to leap. Splaying its arms and legs allowed it to glide to the forest floor before bolting into the underbrush.

Called Microraptor, this chicken-sized dinosaur was one of many feathered dinosaurs discovered in northeastern China starting in the 1990s. These creatures were crucial to understanding how dinosaurs evolved into birds. “They were really what pinned it down,” says Sues. These exceptionally preserved fossils have “full plumage.”

The first such fossil — Sinosauropteryx — only had hairlike fuzz. Found in 1996, this small meat-eater was the first feathered dinosaur found that wasn’t closely related to birds. It offered proof that birds inherited feathers from dinosaur ancestors.

These early feathers emerged millions of years before those used for flight, says Daniel Ksepka. They may have helped early dinosaurs feel their environment. Ksepka studies bird evolution at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Conn. Over time, feathers changed in ways that helped dinosaurs — and eventually birds — keep warm, attract mates and fly.

“When Microraptor was first discovered, it was very unique,” says Ksepka. That’s because this dinosaur had wing feathers growing from its legs. “Some people call them ‘trousers,’ which I think is hilarious,” he says. Researchers suspected the four wings worked together to help the dino fly like a biplane.

Researchers soon started finding these “trousers” in early birds, dromeosaurs and other closely related dinosaurs. Among these were Anchiornis and Xiaotingia, which lived about 10 million years before Archaeopteryx. At one time, researchers suspected these two were among the first birds. It’s more likely, though, they are just close cousins to the ancestor of true birds. But the earliest birds in the Jurassic Period would’ve probably looked very similar.

“Think of the ones in Jurassic Park shrunk down to the size of a crow or pigeon,” says Hues. “And then put feathers on them.”

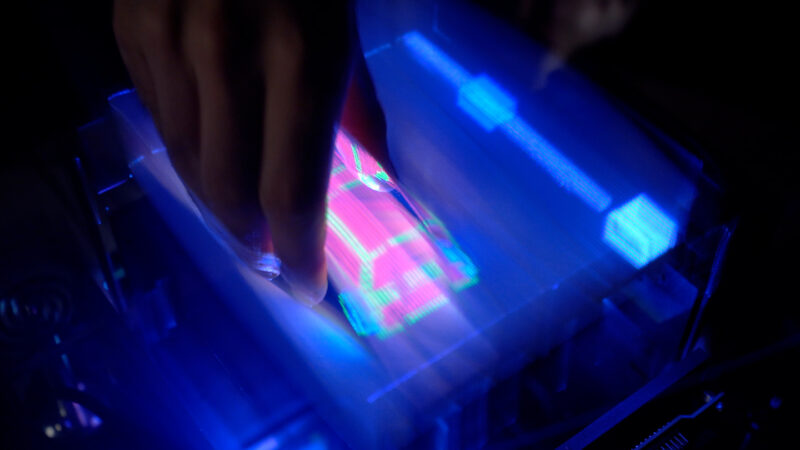

In 2010, researchers at Yale University announced that they had reconstructed the colorful plumage of the feathered dinosaur, Anchiornis huxleyi. They did this by studying the shape of preserved pigment-containing sacs called melanosomes. The results showed that this small theropod may have had a gray body with black-and-white wings. It might have even sported a reddish-brown feathered “mohawk.”MARK P. WITTON/Science Source

O’Connor and her team have been studying these feathers to see how flight might have evolved. They examined the wing feathers of 346 living bird species and found a consistent set of “rules” for birds that could fly: All birds capable of powered flight had nine to 11 feathers. These outermost feathers are attached to a bird’s fused hand bones. These feathers are also asymmetrical, or uneven in shape. In modern birds, this helps generate lift.

Her team then examined fossils from 35 species of non-bird dinosaurs and early birds. “The preservation is good enough that you can actually measure things like asymmetry or actually count the number of feathers,” says O’Connor.

The scientists found that Archaeopteryx and Microraptor seemed capable of flight. Other birdlike dinosaurs did not. Anchiornis — once a contender for the first bird — had about 20 primary feathers. They were also relatively symmetrical. “It’s a very high number,” says O’Connor. “Clearly different from the nine to 11 that you see in flying birds.” Her team published its findings last year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This work is a step toward studying how flight evolved using numbers, says O’Connor. “This is just a problem in paleontology, where basically the past 150 years of research was qualitative.” That means making observations that are hard to precisely measure or analyze using data. Many hypotheses made from observing fossils haven’t yet been tested, she says. “Now, that’s finally happening.”

Snoozing dinos

About 70 million years ago, a flash rainstorm arrived in what is now Asia’s Gobi Desert. In a sandy burrow, a small dinosaur tucked its long legs under its body, resting its head on its right knee. Its fuzzy tail curled around its body. Soon, the dinosaur was fast asleep. Rain steadily gathered above the burrow, causing the sands to shift. Suddenly, the sand loosened, burying the dinosaur as it slept.

This is probably how the theropod Jaculinykus died, says Kohta Kubo. He studies theropods at the University of Tokyo in Japan. Jaculinykus belonged to a group of theropods called alvarezsaurs. These small dinosaurs had long legs and stubby arms ending in a single claw. Kubo discovered the nearly complete skeleton of one during an 2016 excavation in Mongolia. The team described the findings in 2023 in PLOS One.

The fossil showed a meter-long (3-foot-long) dinosaur preserved in a position similar to the way modern birds sleep. Kubo’s team suspects the pose helped smaller dinosaurs conserve heat. The first such slumbering dino was found in 2004. It belonged to Mei long, a dinosaur even more closely related to birds than Jaculinykus.

“Very rarely, we get dinosaurs that are preserved in their life positions,” says Benson. Most fossils get jumbled over time. But some skeletons have revealed complex behaviors, such as brooding over eggs. These remains have shown that “when theropod dinosaurs do those behaviors, their postures are really birdlike,” he says. These remains add evidence that birds inherited these behaviors from dinosaurs.

In the past, such behaviors weren’t viewed as birdlike. In 1923, paleontologists found another Mongolian dinosaur lying directly over a nest containing eggs. The team suspected that the beaked dinosaur died while stealing eggs. So they called the creature Oviraptor, or “egg thief.”

But in the 1990s, researchers began finding related dinosaurs in similar positions. That led scientists to assert that these were probably mother dinos brooding over their eggs. Such findings suggest that some non-bird dinosaurs used their body heat to keep eggs warm, says O’Connor. Such parental care is something that is seen in modern birds but not in other modern reptiles.

New threats

Back at Potomac Outlook Regional Park, Tiger the great horned owl rests on a perch in his enclosure. He looks typical for his species: Two earlike tufts of feathers sprout from his head. Fluffy, cream-colored feet poke out from the cover of his mottled brown and gray wings. But a laminated sign next to his exhibit points out something else: his missing eye.

Over 20 years ago, a car struck Tiger in Virginia. This damaged an eye that was eventually removed. Unlike Smoke or Twiggy, Tiger is too flighty to come with Felperin for raptor shows. “He’s a skittish and nervous bird because he can’t see,” Felperin says.

Raptors often hunt alongside roads, he notes. Food tossed out from vehicles attracts rodents, which attract birds. “A lot of people who are throwing out this food waste think it’s harmless because it’s biodegradable stuff,” says Felperin. But it’s not.

Over 20 years ago, a car struck Tiger. This left the great horned owl with a damaged right eye that was removed in 2023. Owls and other birds of prey often hunt alongside roads. Tossed food from passing vehicles attracts rodents which, in turn, draws these predators. This increases their chance of getting hit.NOVA Parks

Many of the birds we recognize today emerged quickly after the extinction event 66 million years ago that killed off non-bird dinosaurs, says Ksepka. Most modern bird groups were around by about 50 million years ago. Some even sooner. “We have 62-million-year-old penguins,” says Ksepka. These diving birds lived in what is now New Zealand a mere 4 million years after the asteroid impact. “And they’re, like, totally flightless, flippered birds already. That’s so quick.”

“Birds are one of evolution’s great success stories,” says O’Connor. More than 11,000 species exist today. While many fly, others evolved other ways to navigate our world. Emus, ostriches, cassowaries and kiwis dart through forests and grasslands on strong legs. Penguins dive into dangerous oceans after prey.

But now, human activities threaten birds around the world. Researchers and citizen scientists alike are working to conserve important habitats that birds need to thrive.

The traits that make birds unique came from ancient reptiles. They’ve helped make birds some of the most resilient animals to have lived on Earth. “We are so used to thinking that dinosaurs are extinct and they’re part of Earth’s long-past history,” says O’Connor. “But, actually, dinosaurs are the most successful group of land vertebrates on our planet today.”