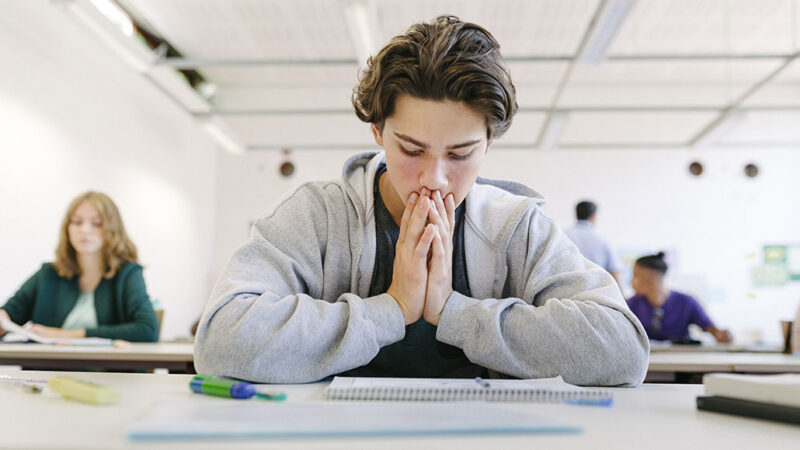

It’s the day of a big test. Your heart is pounding. Your palms are sweating. Your breathing quickens and your stomach suddenly feels full of butterflies. Although these stress responses may not feel good, they are totally normal. They’re your body’s way of sharpening your focus and boosting the energy you have to help you perform well.

When we encounter a big challenge or risk — or become overly excited — our body responds in a way to keep us safe. We’re hardwired for this. These changes supercharge how our body functions.

An increased heart rate and breathing will send more oxygen to our muscles and brain. Our muscles tense so they can react quickly. By sweating, our body attempts to avoid overheating. Our pupils enlarge so we become more aware of our surroundings. And our body releases stress hormones, such as adrenaline and cortisol, to boost our energy and focus.

Explainer: What is a hormone?

Together, these changes are known as the fight-or-flight response. They’re automatically triggered by what’s known as the sympathetic nervous system. It helps us respond to danger or challenges. They give us more power, more speed and agility. All are important for physical activity, says Katharine Meddles. She’s a neurologist for children in Denver, Colo.

This survival mechanism helped our ancient hunter-gatherer ancestors fight or escape from a wild animal — perhaps a saber-toothed tiger. Today, we face very different risks than people did 300,000 years ago. But our sympathetic nervous system remains very important to our making it through challenging events.

It turns on when we play sports, perform or catch ourselves from falling. It motivates us to study or concentrate on difficult tasks. And it turns on when we’re trying something new or talking to someone we like. Activating that fight-or-flight response in short bursts is healthy.

The sympathetic and parasympathetic systems help us respond to serious stressors — but also can kick in for minor ones, such as spilling your drink.

But as soon as the stimulating event is over, our brain normally sends signals to our body to calm down. This turns on a second system: the parasympathetic nervous system. It handles what’s known as the rest-and-digest response.

Here, our heart rate and breathing become slow and steady. Our muscles relax. Stress hormone levels lower, and feel-good hormones — such as oxytocin and serotonin — become somewhat higher. This lets us feel safe. We now can think calmly, digest food and sleep, all processes vital to our brain and overall health, notes Meddles.

Spending time in green spaces can provide big health benefits

You’re in a rest-and-digest state when enjoying downtime with your family and friends. Or when you’re curled up on the couch relaxing with your cat or dog under a favorite blanket. Or when you feel joy and wonder out in nature.

The sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems keep our bodies in balance. Together, they make up the autonomic nervous system. By switching us between rest and action, they work together to help us respond appropriately to the range of situations we experience.

Actions by the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems keep the body balanced as it responds to and recovers from stress. ttsz/iStock/Getty Images Plus

How to calm an overstressed body and mind

But sometimes those systems get out of balance. The sympathetic nervous system may stay active for too long. Or it might get stuck in the “on” position when it’s not needed.

Our world is full of threats. For example, the erratic impacts of climate change not only are hard to predict but also can pose true threats. Social media can pressure us to live or act a certain way. And parents can pressure us to perform well in a competitive environment.

Encountering such conditions may keep your body stuck in fight-or-flight mode.

Worrying about things is not a failing or a shortcoming, says Meddles. “It’s natural” and reflects “the way that our brains are wired.” But too much anxiety can leave you overwhelmed and unable to perform well.

Explainer: What is anxiety?

“How you think and how you feel will show up in your body, because the brain and the body are connected,” says Jin Lee. She’s a psychologist for children in Englewood, Colo. When you’re stressed or anxious, your body might feel as if it’s not getting enough air. You might bite your nails. Or freeze up so that you have a hard time thinking or making decisions. Your mind may even go blank.

Explains Lee, “This is the body’s way of communicating to our brain: ‘Hey, something is not right.’”

At these times, your body’s responses may not serve your best interests.

Fortunately, it’s possible to modify them through practice, says Meddles. In as little as five minutes a day, you can learn to switch from an overactive fight-or-flight mode to a calm body and mind. Preteens and teenagers are in a great position to start learning these skills, she says, because the adolescent brain is so adaptable.

Here are a few simple techniques:

Validate what you’re feeling. Remind yourself that your body responds this way for a reason. You can even talk to yourself, Lee suggests. For example: My muscles are tight. I’m breathing really fast. The reason I do that is because I care about this project and want to do a good job. There’s nothing wrong with me when I do this. My body is reacting. But it is safe and so am I.

Reframe your thinking. You can reshape how you view a situation, says Meddles. Decide if your feelings match what’s happening. Maybe it’s okay to calm down a little.

Focus on breathing. Deep breathing can make you lightheaded, so Lee says to breathe normally but slowly. Pay more attention to breathing out, which turns on our rest-and-digest mode. Activities that naturally focus on exhaling and calming down include blowing bubbles, humming and singing.

Do something fun. Get outside and enjoy yourself, says Lee. Play is especially helpful for someone who is so stressed that they feel frozen or stuck. Play naturally makes us feel better. It also yanks us out of a dormant state, she notes.

Use your five senses. Our senses can help us feel grounded. They refocus our attention and let our brain know we’re okay. For example, watch clouds change shapes in the sky. Listen to birds sing. Pet your dog. Smell flowers or a comforting scent. Taste something pleasant. Getting out in nature — even your own yard — can engage all your senses and calm your mind and body.

Relax your muscles. Tense your muscles for five seconds. Now let them relax. Repeat. This helps calm your body. Says Lee, it also makes you aware of how your body is doing instead of just relying on how you think your body is doing.

The next time you feel overstressed, remember you have the power to calm your body and mind. With a little practice, a few simple tactics can help you calm down.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores