We may be one step closer to adding a new element to the periodic table.

The table currently lists 118 chemical elements. Each has a different number of protons in the nucleus of its atoms. They range from one proton (in hydrogen) to 118 (in oganesson). Some of these elements have been found in nature. Others have been made in labs.

Making new elements with even more protons could help probe the limits of atomic physics.

Let’s learn about the periodic table

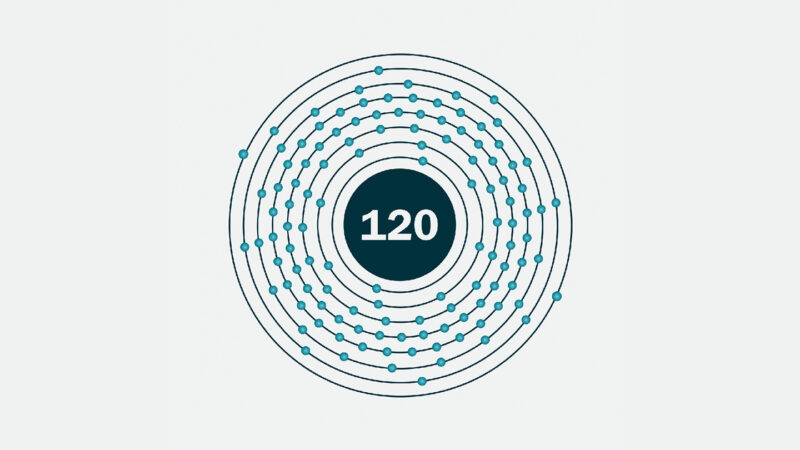

A new study lays the groundwork to create an element with 120 protons. If produced, this element 120 would occupy a new row of the periodic table.

The plan to make that element involves a beam of electrically charged atoms, or ions. Specifically, titanium ions. Scientists would slam this beam into a target of californium atoms.

In theory, that smashup between titanium (element 22) and californium (element 98) should forge element 120. (It’s simple math: 22 + 98 = 120.) But scientists have not used a titanium beam to create such a heavy element before.

So they did a test run.

How to make a new element

In this test, they beamed titanium ions at a target of plutonium (element 94). Their goal: Create livermorium; this element has 116 protons. After 22 days of searching, the team found two atoms of livermorium in the wreckage of their particle smashups.

This helped confirm that a titanium beam could be used to create element 120. But it likely would take about 10 times as long, the team now predicts.

Jacklyn Gates shared these results July 23 at the Nuclear Structure 2024 meeting. It was held in Lemont, Ill. Gates is a nuclear scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California.

Here’s what it takes to add a new element to the periodic table.

The five elements with the most protons so far were all produced using a beam of calcium-48. That’s a variety, or isotope, of calcium with 28 neutrons in its nucleus. To produce those different elements, scientists swapped out the target element. The more protons in the nucleus of the target, the more protons the newly produced element would have.

But that tactic has reached its limit. The next possible targets for calcium-48 are radioactive elements that decay fast. So they don’t last long enough to sift through the debris looking for the new element. Switching to beams of titanium-50 would allow scientists to use more practical targets in their search for new elements.

The target material for element 120 is easier to work with than the one for 119. That’s why scientists are skipping element 119 for now.

“If you want to push above what we currently know on the periodic table,” Gates says, “you need to find a new way of making heavy elements.”