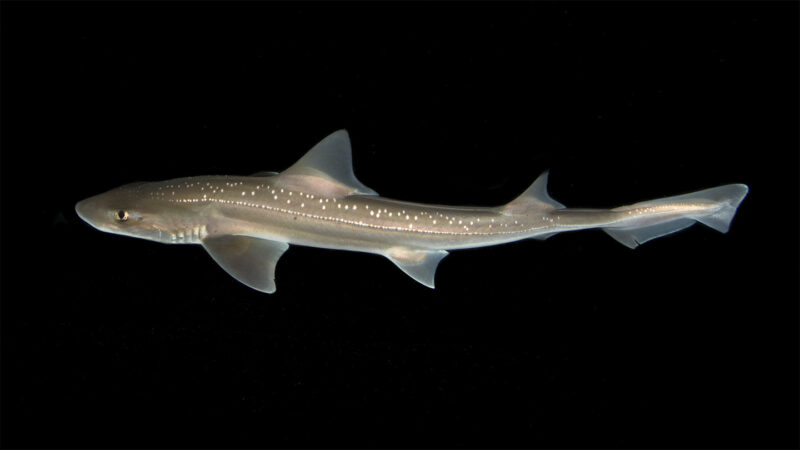

Sharks have a reputation for being silent predators. But an accidental discovery shows the small rig shark isn’t silent after all.

It clicks its short, wide teeth. That chatter appears to mark “the first documented case of deliberate sound production in sharks,” say researchers in the March 26 Royal Society Open Science.

People have been slow in picking up on sound communication between fishes. Some squeak or rumble. But scientists stumbled onto these types of chatter in captive animals. So today it’s no longer a surprise to detect various chirps, hums or growls among the many bony fishes.

Yet an evolutionary sister-branch — sharks, skates and rays — have been slower to get recognized for sounding off. Lacking bones, their skeletons are made of cartilage. Some also sport remarkable senses, such as detecting slight electric fields. In 1971, a clicking was detected coming from cownose rays. Since then, it’s turned up in other rays.

Carolin Nieder is an evolutionary biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts. Back when she was at the University of Auckland’s Leigh Marine Lab in New Zealand, she studied dolphin hearing. To listen, she dangled an underwater microphone into a tank. She also did this as part of her setup to explore hearing in a small shark species called a rig (Mustelus leucticulatus).

Reaching into the tank to grasp one of these fish, she heard “click … click.” After a week or so of tests, the rig still squirmed — but didn’t click. Perhaps the sound was voluntary, a response to stress, she mused.

As a followup, she worked with 10 sharks. Among them she recorded multiple clickity bouts. They averaged about nine clicks during a 20-second grasp. The sounds come, she proposes, from clacking together their short, wide teeth with cusps. Those chompers are great for cracking crustaceans’ shells. Rows of these teeth emerge from gum tissue. It reminded Nieder of stones set in a mosaic.

Wiggling doesn’t seem important: She heard the sounds when a test shark writhed in her grasp and when it held still. She proposes that sharks click by “forceful snapping.”

The idea still needs formal testing, she cautions. What she actually measured was the hearing range of the sharks, which is restricted to below 1,000 hertz. Human hearing, in contrast, ranges up to 20,000 hertz.

Sharks are sensitive to their watery world in other ways, though. For instance, they can detect the tickles of changing electric fields. Yet “if you were a shark, I would need to talk a lot louder to you than to a goldfish,” Nieder notes. “The goldfish would pick up if I whisper … and the shark was like, can you speak up, please?”