Mayonnaise is useful for smearing on sandwiches and prepping potato salads. But scientists are now using it to study nuclear fusion.

How mayonnaise behaves can vary. If jiggled gently, it returns to its original shape. That’s called elastic behavior — like how an elastic hair band will return to its original shape after you stretch it. But fling the mayo forcefully and it takes on plastic behavior. That means it permanently changes its shape or can even break apart. (You’re probably more familiar with the term “plastic” to describe the material that makes up soda bottles, LEGOs and more. The two terms are related. Plastic, the material, is named after its ability to be molded or deformed into various shapes.)

This elastic-to-plastic morphing also can also take place in tests that use lasers to kick off nuclear fusion. That’s the process where slamming two lightweight atoms together hard enough can make them merge. The mass of this combo is less than the sum of each starting atom. That’s because some of that mass is converted into energy. So the process releases an enormous amount of energy.

Scientists want to learn how to control fusion so they can one day use it to generate electricity.

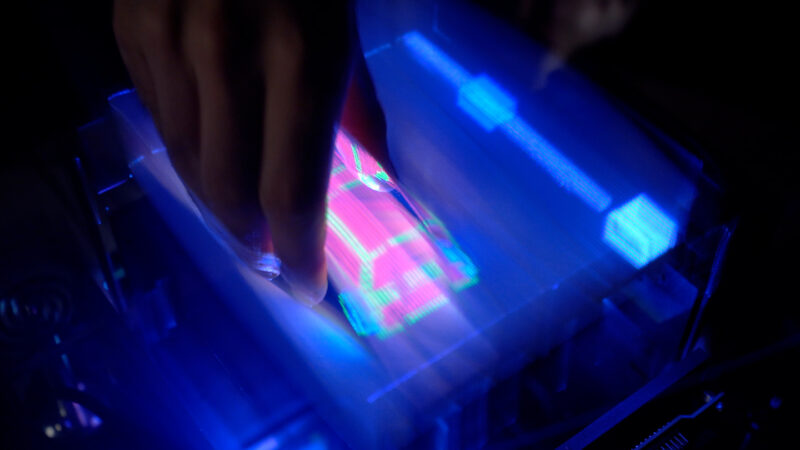

Scientists have been working to ignite a fusion reaction in the lab that releases more energy than went into it. Last December they succeeded. Researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California beamed 192 lasers at a small chamber containing fuel. This raised the pressures and temperatures so high inside the fuel that the nuclei of its atoms fused. And those fusion reactions released more energy than had been needed to set them off.

But it’s difficult to study how materials behave under the extreme conditions required for fusion. And that’s where the mayonnaise comes in.

The behavior of the fuel capsule in fusion experiments, it turns out, has a lot in common with mayonnaise. The fuel capsule is a metal or other material that contains a gas (the fuel). When lasers hit the capsule, it melts. The melty capsule can now switch from elastic to plastic.

The molten capsule has some properties of a solid. Like gloopy mayo, it doesn’t flow on its own. Under enough force, however, it can break apart. If the capsule becomes plastic before fusion occurs, the gas could escape. And that could prevent fusion from taking place.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Two mechanical engineers at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pa., wanted to understand that better. So they looked at how mayo mixes with a gas — air. Aren Boyaci and Arindam Banerjee spun a wheel into which they’d dropped dollops of mayo. The centrifugal force of the spinning wheel accelerated that mayo into the air. Here, the mayo acts like the melted capsule, and the air acts like the gaseous fuel.

The scientists observed the glob while the wheel was spinning. They looked at it again after it stopped. They checked whether the mayo had returned to its original form, changed shape or broken apart. This determined the border between its elastic and plastic behaviors, they explain in the May Physical Review E.

Working with mayo does have one drawback. When you show up in the supermarket checkout line with 48 containers of mayo, you’re bound to attract attention. “We sometimes get a lot of questions from the grocery stores,” Banerjee says, asking “why we are buying that much mayonnaise.”