Our brains are very flexible. Some people use their brains to create art. Others use them to solve math problems. Some do both — plus a host of other actions.

Our brain is made up of two halves called hemispheres. The left and right sides are symmetric, meaning they look more or less the same. The major brain structures that control how we think, move, feel and see are found in both halves.

But the sides can act separately. For instance, the left side of the brain controls vision and movement on the right side of the body. And vice versa. Some functions, such as speech, can be controlled more by one side of the brain than the other. This has led some people to suggest that the two halves are specialized.

People sometimes describe those of us who are more creative as being “right-brained,” and those who are more logical as “left-brained.” This became a very popular idea about how the brain works. But it isn’t really true.

To understand where it came from, we have to go back 70 years.

Right-brained or left-brained? Both! Although some functions seem based more on one side of the brain — a concept called lateralization — most things we do use structures in both halves.

Where did this idea come from?

The theory about left and right brains emerged from work that started in the 1950s.

Roger Sperry was a neuroscientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. He got curious about how the two sides of the brain interact. He focused on a thick bundle of nerve fibers that joins the two halves. It’s called the corpus callosum and in people it contains more than 200 million nerve fibers.

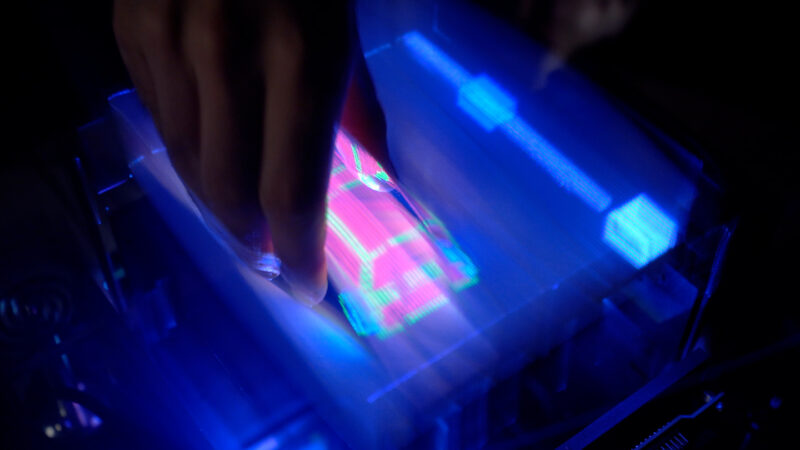

Brain imaging technologies can reveal nerve connections throughout the brain. A large bundle of fibers called the corpus callosum — seen here as vertical yellowish lines — links the two hemispheres.SEBASTIAN KAULITZKI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

This connection helps the brain’s two sides communicate and work together. But doctors had discovered that cutting the corpus callosum could help treat severe cases of epilepsy. In this disorder, excess nerve-cell activity can overwhelm the brain. It’s been described like a lightning storm inside the head. Too much nerve-cell firing can cause harmful seizures. Cutting the corpus callosum quieted them. And it didn’t seem to have a big effect on normal brain function.

That splitting the brain didn’t seem to cause problems fascinated Sperry. To better understand why, he started working with people who had gotten their corpus callosum cut.

At a loss for words

Sperry asked these volunteers to cover one eye at a time. Then he showed them a series of words. The people could only recall words they viewed with their right eyes, not their left. When shown objects, people could draw things they saw with their left eyes but could not describe them in words.

These results suggested that the ability to use and understand language is based in the left side of the brain.

This finding made sense for other reasons, too. From other studies, researchers knew about two parts of the brain important for language. They are called Broca’s (BRO-kuhz) area and Wernicke’s (WUR-nih-keez) area. Both are usually found on the left side of the brain.

Broca’s area largely controls language. It’s found on the left side of the brain in a region called the inferior frontal gyrus, highlighted here in orange.Kateryna Kon/Science Photo Library/Getty Images Plus

Sperry’s “split-brain” research changed how we thought our brain worked. Indeed, he would share the 1981 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for his work. But the idea of right- versus left-brain skills also caught people’s imaginations. An article based on Sperry’s work had been published in the New York Times Magazine in 1973. It took ideas from his findings and other case studies and ran with them. It claimed skills such as musical ability were controlled entirely by the right brain.

In this way, important research gave way to speculation.

Brain imaging reveals connections

In fact, this early research had one huge limitation: Scientists back then had no way to look inside a living brain.

Now, researchers have several tools that can image the working brain. One is functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. It can track blood flow in the brain. Active brain cells need lots of oxygen, which is carried by blood. So high levels of blood flow are used to pinpoint regions where the brain is active.

In 2013, researchers used MRI to scan the brains of more than 1,000 kids and young adults. They measured whether some brain functions seemed isolated to the left or right sides. And a few functions were tied more strongly to one side, these scans showed. Among them was language, which supported Sperry’s findings from decades earlier. But most brain networks bounced between both hemispheres.

That disproved the idea that only the right hemisphere is at work when you perform music or create art, says Diana Sarko. “That’s just not true. [Activity] is very, very distributed.” And, she adds, “Thank goodness it is, because both sides of the brain have a lot to offer.” Though not part of the MRI work, Sarko studies the brain at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale.

This video debunks the myth about analytic “left-brained” versus artsy “right-brained” people.

Michelle Ellefson agrees. The theory that one side of the brain can control general traits like creativity or logic is out of date, she says. A neuroscientist, she works at the University of Cambridge in England. “The thinking now,” she says, “is that although there may be one area largely responsible for some sort of skill, it doesn’t work on its own.” Brain imaging shows that “everything’s interconnected.”

Not only do brain areas work together, but sometimes networks also change or move. Such shifts may be seen in response to injury. And they give further evidence that many functions aren’t limited to specific areas of the brain.

Some functions are controlled more by regions on one side of the brain than the other. But traits like creativity and logic are far too complex to use just one brain area. In fact, any time you create a painting or solve a math problem, lots of areas on both sides of the brain team up. So the next time a quiz or a friend tells you that you’re “left-brained“ or “right-brained,” remember: You have your whole brain to thank for all the amazing things you can do.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores