In the Iron Man movies, Tony Stark’s lab is full of floating computer displays. With these midair graphics, he can see his super-suit designs in 3-D. He also can grab hold of the visuals and manipulate them. A new device brings such sci-fi graphics closer to reality.

The device renders virtual 3-D objects in midair that users can drag, scale and rotate with their fingers. Such interactive visuals — which can be seen without a virtual reality (VR) headset — could lead to a new type of hands-on museum exhibit or virtual pets. They also might be used to make 3-D art or video games.

Researchers shared their new tech April 30 at the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. The meeting was held in Yokohama, Japan.

In the past, machines have displayed 3-D objects by moving a flat screen up and down. Each 2-D slice of the object would be projected onto the screen at different heights. When the screen moves extremely quickly, those slices blur together. As a result, they look like one solid shape.

“It’s like a real 3-D object. You can see it from all directions,” says Elodie Bouzbib. She studies human-computer interactions at the Public University of Navarre. That’s in Pamplona, Spain.

Making hands-on graphics

One problem with past 3-D displays was that users couldn’t touch the fast-moving screen without hurting their hand or damaging the device. To interact with the visuals they had to use a keyboard, 3-D mouse or some other indirect technique.

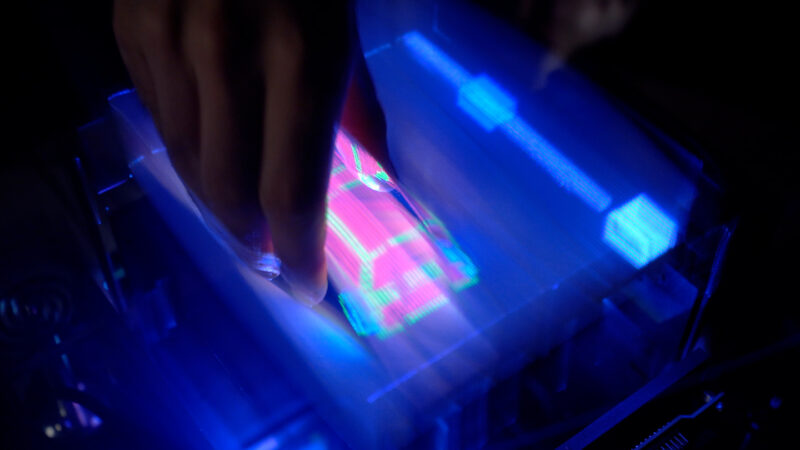

Bouzbib is part of a team that decided to replace the flat screen with strips of a stretchy material. Now, users can reach into the display — their fingers slipping past the moving strips — to handle virtual objects.

The team tested strips of different materials to see which might work best. Some, like Spandex, stretched out too easily. Others, like plastic lanyards, hurt to touch when they whipped up and down. Still others, such as silicone, reflected too much light to clearly display projected images.

In the end, strips of elastic — like those used in the waistbands of stretchy pants — won out. “They were a good compromise between all the properties,” Bouzbib says. Two cameras tracked users’ fingers within the display. This let the graphics respond to pinching, swiping, spinning and other gestures.

Playing around — for science

Eighteen volunteers tried out the new device. They selected, moved and traced virtual objects with either their fingers or a 3-D mouse.

People were able to navigate the display faster and more precisely with their fingers. Most also said the hands-on method felt easier and more natural than using a mouse. That was true even though some had been concerned that the display would feel unpleasant to touch. “It feels really soft, actually,” says Bouzbib. “It tickles a bit.”

“What really gets me excited about this research is that the display is reasonably sized and interactive,” says Tatsuki Fushimi. An engineer at the University of Tsukuba in Japan, he did not take part in the work. But he has created 3-D graphics using particles levitated by sound waves. You can touch those displays too, he points out. But it’s hard to use levitation to make images bigger than about one centimeter (0.4 inch) across.

The elastic-band display is 19 centimeters (7.5 inches) wide and 8 centimeters (3 inches) deep. That’s about the size of a square Tupperware container. “Now, people can start to experiment and play around with it,” Fushimi says. That should invite fresh ideas on how to use this technology.

Volunteers in this study suggested using it for control panels for surgical robots. They also thought it would work well for viewing products in 3-D while shopping online.

“If you want to make it bigger, it’s probably going to face issues,” Fushimi says of the elastic-band setup. “Imagine it room-sized. Then you can no longer reach through the display.” In other words, it wouldn’t work for building something like a Star Trek holodeck. But Fushimi could imagine it being scaled up to a desktop-sized device.

One day, Bouzbib would like to add touch — or haptic sensations — to the display. A focused beam of ultrasound waves might create sensations at a users’ fingertips as they handle virtual objects.

Her team also is brainstorming how to project images onto a layer of gas rather than elastic strips. Such an intangible material might offer more seamless interactions with midair graphics.